Introduction

A considerable part of learning the rules of appropriateness is among other things, to know how to use politeness expressions in daily social interactions. Politeness in its relation to speech acts has long been a great concern of many linguists all over the world. It is nowadays a concept which is heavily studied in cultural studies and pragma-linguistics. Consequently, any research that identifies the use of speech act realization strategies can be extensively helpful to understand the culture of its speech community. Pragmatics, i.e. language in use, has been highly concerned with the notion of politeness through speech act theory. As a community that is claimed to have strong social ties among its members, speakers of Arabic are expected to exhibit differences which distinguish them from speakers of other communities. This study widens the scope of pragmatics by investigating politeness in Algerian Arabic. The aim of this article is to show some major problems of linguistic politeness in connection with translation studies. This study examines some Algerian Arabic politeness expressions identified by the researcher as highlighting pragma-religious difficulty to translators of Arabic texts into English. Our concern here is only with individual expressions which are drawn from everyday conversational behaviour. As for the choice of religious politeness expressions rather than any other formulas, it is motivated by the intuition that underlying principles may govern politeness phenomena in human languages (Brown and Levinson, 1987), the means whereby politeness is encoded linguistically often vary from one language to another, especially where religion is considered a standard in expressing politeness. Therefore, Algerian Arabic politeness formulas that encapsulate in them religious background are expected to be rich ground for pragma-religious failure. In other words, the purpose of this study is to examine to what extent a failure to grasp the pragmatic and cultural condition of the use of politeness expressions may lead translators to render Arabic religious formulas in English inappropriately. The most serious problems in translation are, in fact, those difficulties arising from differences of culture (Brown & Levinson, 1987). However, the question is: how can a translator bridge the cultural gap in rendering a religious Arabic expression in English without committing a pragmatic failure which usually distorts the message.

1. Linguistic Politeness

Politeness is an essential part of pragmatics. The theoretical underpinning of politeness phenomena begins in the fleeting reference made by Grice and Searle to politeness in their work. Grice (1989:.28) notes that “there are, of course, all sorts of other maxims (aesthetic, social, or moral in character), such as ‘Be polite’, that are also normally observed by participants in talk exchanges and these may also generate nonconventional implicatures”. Searle (1975:.60) also observes that “The chief motivation though not the only motivation for using these indirect forms is politeness”. The attention exhibited within pragmatics towards linguistic politeness theory over the last decades has resulted in the emergence of a vast eclectic literature around it. Linguistic politeness theory can, in fact, be considered almost as an independent field of study of pragmatics, and more specifically, it is the social approach to pragmatics. The term “linguistic” is used here as a modifier for “politeness” mainly to emphasise that the concept of politeness is necessarily related to verbal interaction, which is different from non-verbal behaviours defined in terms of social norms or etiquette, such as giving a seat to an elderly person on a bus.

1.1. Islamic Culture and Politeness Expressions

The impact of religion on human history and identity is stronger than anything else; it has prompted people to settle, to go to war, and has inspired some of the most precious human achievements in art, architecture, etc. It usually provides guidelines and advice about good and evil. At the same time, it provides guidelines for a just society and proper human conduct Islamic culture had and is still having an influence on the speech of Arabic speakers.

Muslims believe that the Quran is the basic source of Islamic teachings; it deals with all the subjects that concern people as human beings: wisdom, worship, and law. It is, therefore, not surprising that religion can also be traced in our everyday speech, not only when we are speaking about religion, but in casual conversation. Thus, in the Arab world, religion is apparently one of the sources from which people gain their cultural repertoire. “This sociolinguistic phenomenon is regarded as unique and related to Arabic language” (Morrow and Castleton, 2007:.209).

1.2. Pragmatic Failure

Etymologically, the term “pragmatic failure” was firstly coined by Thomas (1983) in an article entitled “Cross-cultural Pragmatic failure”, where she provides definitions and classifications to the term. Since then, pragmatic failure has become the core of cross-cultural pragmatics. According to Thomas (1983), pragmatic failure is generally defined as “the inability to understand what is meant by what is said” (1983:.82) Closely related to pragmatics are two basic notions that need to be identified here, i.e. linguistic competence and communicative competence, since full mastery of these two competences helps avoid pragmatic failures. Linguistic competence is simply defined as the knowledge of language use and users, including interlocutors’

“ability to create and understand sentences, including sentences they have never heard before, knowledge of what are and what are not sentences of a particular language, and the ability to recognise ambiguous and deviant sentences” (Lou & Goa, 2011:.284).

In other words, linguistic competence is the mastery of a foreign language “standard pronunciation, accurate grammatical rules and vocabulary” (ibid). In addition to the abstract knowledge of linguistic properties, pragmatic linguistic competence is more concerned with the interlocutor’s ability to use a language communicatively (Amaya, 2008). Having realised that, the notion of linguistic competence, proposed by Chomsky, is inadequate, Hymes (1971) coined the term “communicative competence”, which refers to the mastery of both linguistic competence and sociolinguistic knowledge of language in a given context. Accordingly, interlocutors in cross-cultural communication must have communicative competence including the socio-cultural rules of both the source and the target languages. In this way, interlocutors can avoid the possibility of native language transfer, i.e. pragmatic transfer, during cross-cultural communication and the probable occurrence of pragmatic failure (Hashimian, 2012). Based on Hymes (1971), Lou & Goa (2011) has thoroughly defined communicative competence as the knowledge of not only if something is possible in a language, but also the knowledge of whether it is feasible, appropriate or, done in a particular Speech Community. It includes, 1) formal competence – knowledge of grammar, vocabulary, phonology and semantics of a language. 2) socio-cultural competence – knowledge of the relationship between language and its non-linguistic context, knowing how to use and respond appropriately to different types of Speech Act, knowing which Address Forms should be used with different persons one speaks to and in different situations, and so forth.

1.3. Lingua-Pragmatic Failure in Translation

Lingua-pragmatics is a field of linguistics that studies “fixed” language forms having fixed socio-pragmatic meanings (Shammas, 2006). Lingua-pragmatics is useful in developing social relationships through culture-specific politeness in interpersonal communication. These “fixed” forms define the speaker’s attitude towards the hearer but also represent such norms of speaker’s language through which the speaker could use the language to request, congratulate, greet, and apologise with other members of their community. If the speaker fails to use appropriate forms corresponding to these norms, it would be considered as a pragmatic failure. All such forms are within the scope of lingua-pragmatics. Speakers with the same cultural background and who speak the same language can easily understand these lingua-pragmatic forms, but non-native speakers face difficulties in understanding the message carried by these forms. Hence, lingua-pragmatic forms can be said to be totally language-specific and culture specific. One of the forms of lingua-pragmatics is expressions of politeness in multiple situations.

Lingua-pragmatic failure is the interpreter’s failure in conveying the intended meaning (pragmatic knowledge) of the message as the result of the inappropriate use of language. Pragmatic knowledge includes the ability to know the relationship between the propositional content (i.e. semantic meaning) and illocutionary force (i.e. pragmatic function) of any politeness expression. Sometimes the relationship between the two is very obvious and easy to determine as in the case of the Arabic expression /lila mabrouka/ (ليلة مبروكة) “have a blessed night”. In other cases, however, it is not possible to relate the propositional content to its function. One may need to learn the conventions and conditions of use of an expression like /flæ:n ʕaba bæ:sek/ (فلان عبى باسك) literally meaning “so and so took your suffering” politely implicating that the person has died.

A difficulty may also arise when the same expression is used to perform more than one illocutionary act in different situations. The expression /nʃallah/ (انشاءالله) literally meaning “if God permits” can be interpreted differently. If the phrase is uttered as a response to a command by a speaker of a higher social status or of an older age, it would carry the force of a speech act and forms a commitment to execute the command quickly; it would be approximately translated as “definitely” or “absolutely”. However, if the same phrase is used in response to a request by someone, who is of equal or inferior status, then it would not necessarily constitute a moral obligation, and it would better be translated as “ok”, “alright”, “I’ll see what I can do”, “I’ll let you know”.

2. Research Methodology

The current research focuses on the pragmatic failure in interpreting religious formulas. The researcher used a quantitative and descriptive analysis in translating politeness expressions from Arabic into English.

-

Participants: The study sample which includes males and females was selected randomly. It consisted of (30) MA students holding a degree in translation and reading for their master’s degree in translation studies at the University of Oran. The participants have been studying translation and pragmatics for about three years and must have acquired the necessary knowledge which enables them to be aware of the role of pragmatics in the field of translation.

-

Instruments: The data was collected by means of a test given to students who were asked to translate different religious politeness expressions pertaining to four speech acts: requests, thanking, condolences and congratulating speech acts, namely religious politeness expressions. Thus, the participants were asked to provide their own translations of various expressions from Arabic into English.

The researcher will attempt to find out the pragma-religious failure that MA students of the Department of translation may commit in translating religious expressions from Arabic into English. This test was designed for several purposes such as finding out whether students use form-based translation (literal translation) or meaning-based translation (pragmatic translation) and determining the effects of these shifts on the quality of translation. Thus, the method followed in evaluating and analysing the data consisted of both the quantitative and qualitative procedures. In other words, graphs were drawn to show the number of form-based translation (literal meaning) and meaning-from translation (pragmatic meaning) the students had in translating the expression. This is called a pragmatic translation deviation, which is different from a grammatical or even semantic error. On another hand, tables were drawn as answers to the translations which were particularly analysed on the cultural level, or more specifically, lingua-pragmatically, i.e. on the level of the close interface between language and culture.

3. Results and Discussion

The translations of the religious politeness expressions by the subjects of this research have been analysed and discussed in an attempt to examine the area of politeness translation and to investigate the major causes of inappropriate translation. The goal of a good translator is to reproduce a text in the target language which communicates the same message as the source language but using the natural grammatical and lexical choices of the target language. The misconception of transferring meaning can happen.

In this section, we will discuss some pragma-religious failures in translating Arabic politeness expressions into English. The tables below contain some of the lingua-pragmatic religious polite formulas in Arabic with a form-based translation (literal translation) into English and a meaning-based translation (pragmatic translation) equivalent in English when available. It might be beneficial to examine some of these expressions and their translation from Arabic to English to see the differences between both languages and try to find the equivalent of each form and its realization. As part of the data collected, the translated Text included about 23 expressions and was translated by 30 students. All in all, the erroneous utterances that deviated from the meaning as intended in context were labelled as form-based translation (see the Tables below).

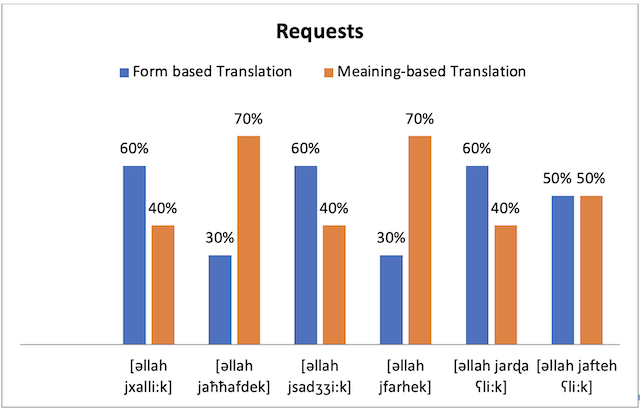

3.1. Requests

Requests are one of the many speech acts used quite frequently in every day human interaction. In Brown and Levinson’s (1987) terms, requests are face-threatening acts (FTAs), which threaten the hearer’s negative face. So, those who perform a request need to reduce the level of imposition created by an act being requested in order to save the hearer’s face and, at the same time get his/her compliance with a request.

|

Requests |

Form-based Translation |

Meaning-based Translation |

|

[əllah jxalli :k] الله يخلّيك |

May God preserve you |

Could you…? |

|

[ǝllah jaħħafdek] الله يحفظك |

May God Protect you |

Could you please…? |

|

[ǝllah jsadʒʒi :k] الله يسجّيك |

May God make you succeed |

Do you mind…? |

|

[ǝllah jfarhek] الله يفرحك |

May God Make you Happy |

Would you kindly …? |

|

[ǝllah jarɖa ʕli :k] الله يرضى عليك |

May God be happy with you |

Could you…? |

|

[ǝllah jafteh ʕli :k] الله يفتح عليك |

May God make things easy for you |

Could you…? |

Table 1 Requests and Politeness

Most subjects (60%) opted for “May God preserve you”, “May God make you succeed”, “May God be happy with you” as a form-based translation of the following formulas respectively [əllah jxalli :k] الله يخلّيك, [ǝllah jsadʒʒi :k] الله يسجّيك, [ǝllah jarɖa ʕli :k] الله يرضى عليك. The translation of those formulas is inappropriate, as it is culturally and linguistically insufficient for the target reader to grasp the intended meaning of the formulas. This is because the implicature encapsulated in the Arabic formulas, that is, implicating requests, is completely missed in English if the translator relies only on the semantic meaning, thus entailing the praise of God independently of the speech act of requests.

Many students translators (70%) seem to have understood the illocutionary force intended by the following formulas [ǝllah jaħħafdek] الله يحفظك and [ǝllah jfarhek] الله يفرحك when used as requests through the use of modals, e.g. “will, would, could, etc.” and question forms to minimise the imposition and maximise the factor of optionality in favour of the addressee.

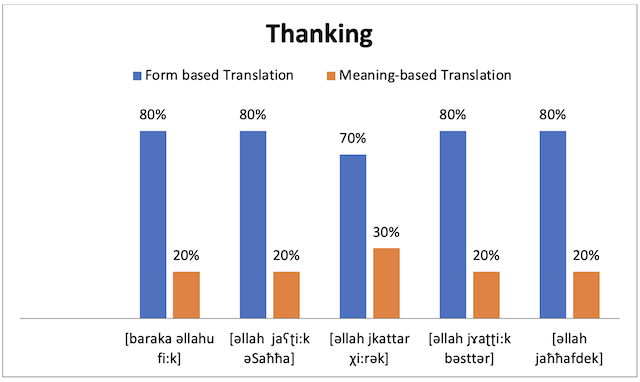

3.2. Thanking

Thanking or expressing gratitude is a convivial speech act which is frequently used in daily communication, for it is the universal ritual and convention that all the people around the world observe. From the following table, it is noticed that Arabic is rich in polite expression of thanking.

|

Thanking |

Form-based Translation |

Meaning-based Translation |

|

[baraka əllahu fi : k] بارك الله فيك |

Bless you |

God Bless you |

|

[əllah jaʕʈi :k ǝSaħħa] الله يعطيك الصحّة |

May God give you good health |

Thank you |

Table 2 Thanking

The students translators used the same formula, namely, “God bless you” for both form-based translation (80%) and meaning-based translation (20%) for the expression [baraka əllahu fi : k] بارك الله فيك. A contrast can arise when two languages contain routines which are semantically similar but differ in the functions they can fulfil. For instance, the expression “God bless you!” is used in both cultures, but for different effects: in English, it is usually said to somebody sneezing; in Arabic, it is an expression of gratitude said in return for a service or kind act. It is noticed that Allah is in almost every aspect of real-life situations, while it is not exactly the case in English. For instance, it is a matter of routine politeness that, after sneezing, the Arab sneezer should praise Allah by invoking /əl ħamdu lillah/ الحمد لله (praise be to Allah). In English by contrast, the sneezer has no formulaic expression to use after sneezing. Thus, it may also happen that a formula is required in one language whereas in the other no formula is required at all in the corresponding situation.

It seems that there is no one to one equivalent term in English for the different gratitude formulas. This is the reason for providing a same word translation “thank you” for different lexicons by (20%) of the respondents. The translation of thanking formulas seems to be nearly impossible because of the specific religious connotations inherent in religious expressions and the pragmatic functions they exhibit.

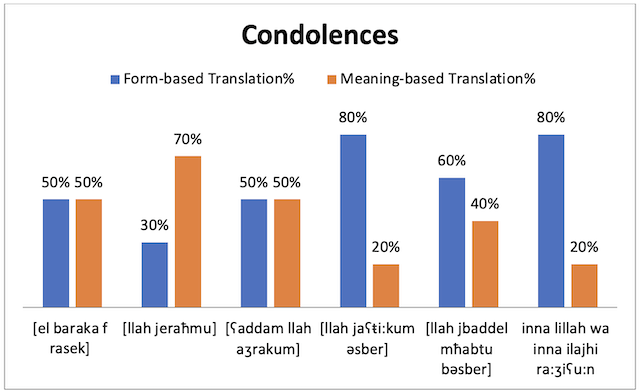

3.3. Condolences

In condolences, whereas in Arabic there are several expressions that designate the degree of loss (death/failure, etc.), the formality of the situation, and the interpersonal level of relation, in English, such expressions are few and lack the level of formality expressed in Arabic utterances. Thus, all the condolence expressions used in Arabic are formally equivalent to only one or two English expressions:

|

Condolences |

Form-based Translation |

Meaning-based Translation |

|

[el baraka f rasek] البركة فراسك |

Blessing on yourself |

Sorry to hear about your loss |

|

[llah jeraħmu] لله يرحمو |

May God bless him |

May God have mercy on him! |

|

[ʕaddam llah aʒrakum] عظّم الله اجركم |

May God increase your reward |

Sorry to hear about your loss |

Table 3 Condolences

A large number of students (50%) adopted, more or less, form-based translations that were inappropriate and too direct. They sacrificed politeness in the target culture as they tended to paraphrase the source formula as can be illustrated in:

-

[el baraka f rasek] البركة فراسك “Blessing on yourself”

-

[llah jbaddel mħabtu bǝsber] لله يبدّل محبتو بالصبر “May Allah replace his love with patience”

These politeness formulas can be simply rendered as: Please accept my sincere condolences. Thus, most of the students (80%) did not maintain the polite speech act of condolences in the target language. They gave their own interpretations of the implicated meaning, namely, meaning-based translation of the formulas.

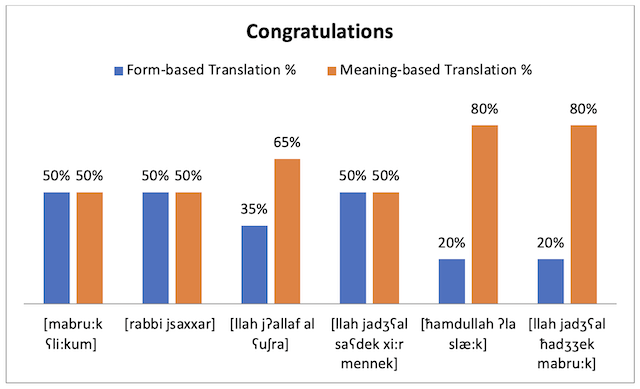

3.4. Congratulations

Congratulations may be classified under the category of expressive because in performing such acts, the speaker expresses his feelings. Congratulations are uttered in the context of happy events, such as linguistic formulas used in weddings, births, religious festivals – all occasions for public as well as private joy – in traditional Algerian society, which has a rich historical heritage in this regard. Algerian marriage ceremonies have a unique identity, which binds together the different practices followed in the region. The following religious expressions are noticed:

|

Congratulations |

Form-based Translation |

Meaning-form Translation |

|

[mabru: k ʕli: kum] مبروك عليكم |

May you be blessed |

Congratulations! |

|

[rabbi jsaxxar] ربّي يسخّر |

May God bless your union |

May the love you share today grow stronger |

|

[llah jʔallaf al ʕuʃra] الله يألّف العشرة |

May Allah bless your union |

Congratulations! |

Table 4 Congratulations

The analysis of the students’ translations of congratulations formulas showed that 50% of them were form-based translations. Thus, they failed to translate most congratulations formulas and often did serious damage to the pragmatics of the discourse as can be exemplified in:

-

May you be blessed

-

May God bless your union

-

May God make your luck i.e. husband better than you

Such cases of non-equivalence may pose various problems for the language translator. If translators attempt to translate and use their first-language formula in the target language, the result may be a fairly appropriate contribution to the conversation, one which seems exaggerated or stylistically odd, or one which seems to make no sense at all.

(80%) of the students translators used meaning-based translation “congratulations!” for the formula [ħamdullah ʔla slæ :k] الحمد لله على السْلاك said to a woman who has just had a baby and [llah jadʒʕal ħadʒʒek mabru :k] الله يجعل حجّك مبروك said to one about to make a pilgrimage to Mecca. On the other hand, only (20%) used form-based translation. Thus, one of the most striking contrasts between the content of the Arabic and English routines is that many of the Arabic expressions involve references to religious concepts, where the corresponding English ones do not.

The present section deals with the major pragma-religious problems in translating Arabic religious expressions. For the purpose of the study, the term religion means the feelings, emotions, attitudes, and moral traditions expressed in the formulas, which manifest themselves in socio-religious system of the Arab culture. According to Piamenta (1979) Islam was the one major factor that saved the Arabic language from degeneration. Interestingly, Allah which is frequently mentioned in Arabic politeness formulas dominates the Arabs’ social relations. These religious politeness expressions are culture specific and language specific in their use, so that, the translation equivalent in most cases is only a rough approximation and does not yield the effect intended by the speaker. As a matter of fact, there are hundreds of similar expressions that reflect the influence of Islam on native speakers of Arabic, thus, revealing Arab’s great veneration of Allah. This belief is constantly consolidated by worshipping him, in praising and thanking him.

It was noticed that the translator may prioritise religious background for the sake of creating the equivalent translation. In other words, Arabs resort to fixed linguistic expressions for conveying a polite attitude. Conversely, the use of models for requests is a more natural form of speech act in English, whereas religious politeness expressions are much more indicative in terms of the source language culture.. Thus, Arabic and English present cultural and social differences, and these differences result in a considerable disparity in the level of lingua-pragmatic expressions and their translation.

Conclusion

As the discussion of the data in this study implied Arabic and English present cultural and social differences and this result in a considerable difference on the level of lingua-pragmatic expressions and their translation. For instance, Arabic has quite elaborated sets of polite lingua-pragmatic forms, while English has a limited number of polite formulas. The intimate relationship between family members, relatives and neighbours might be the reason why Arabic is rich in polite expressions of requests, thanking, congratulations and condolences. In Arabic these expressions are composed of different words with different semantic and linguistic characteristics. Thus, the translation of politeness expressions is fully pragmatic and contextual rather than linguistic and semantic. This is why the translator needs to pay more attention while translating these expressions and their intended meaning from Arabic to English and vice versa. In summary, such language forms as those studied under lingua-pragmatics are mostly language-specific in structure, culture-specific in communication, and very difficult to translate appropriately. Above all, negotiating their meanings leads to pragmatic failure. Therefore, the only way to avoid pragmatic failure in using them in a foreign language is by learning the cultural code that matches the use of a possible equivalent in the target language.